Description

|

Lamborghini

part number

|

OEM manufacture

part number

|

notes

|

|

|

chain, cam - 2ea

|

MD-02702

|

Regina

ASA 35, made in Italy, double strand, rivited

construction,

3/8

pitch, 3/16 roller width, .200" roller dia, |

93 links + master. |

|

|

Cup, cam - 24ea

|

MD-02917

|

|

|

Countach, Jarama,

Espada, Miura, Alfa

|

|

shim, valve adjust

|

MD-01072

|

8mm x 1.5 thru

3.5mm fits Lambo 1964-1989 v12

Alfa shims, valve lash caps 8mm

|

|

Alfa

1.5-2.5

Alfa

2.525-3.0

|

|

keepers, valve - 48ea

|

MD-00233

|

|

|

|

|

keeper, valve - 24ea

|

MD-00228

|

|

|

|

|

spring, inner valve

|

MD-01020

|

46.5mm long, 22mmID,

3.425mm wire, 6.33coils

|

|

|

|

spring, outer valve

|

MD-02033

|

46.5 long, 32 ID, 3.93

wire, 5.5 coils

|

|

|

|

washer, valve spring

shim

|

MD-02903

|

|

|

|

|

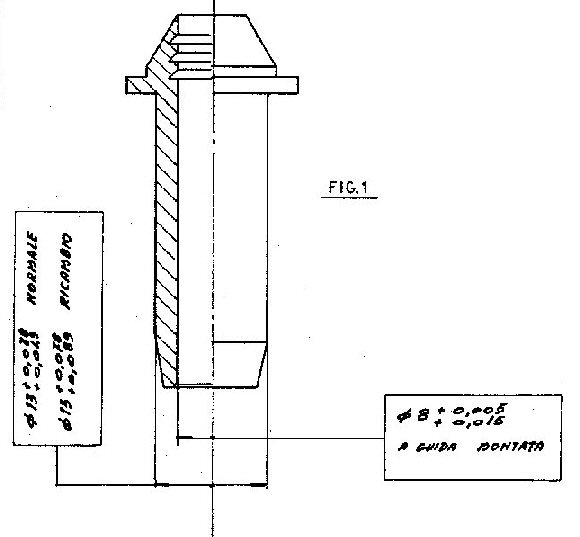

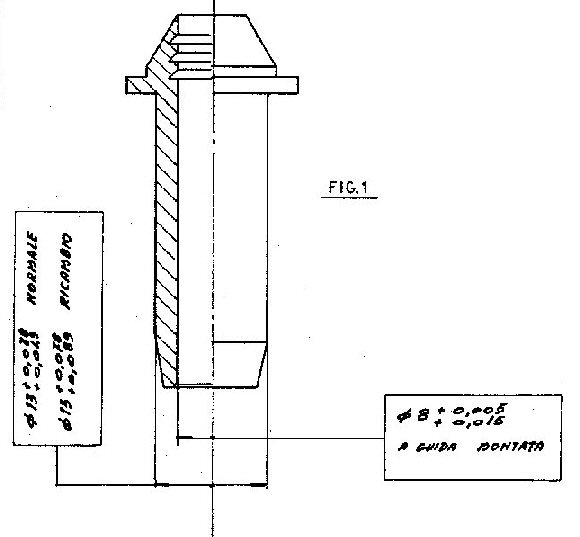

guide, valve

|

MD-01032

|

|

|

|

|

seal - oring?

|

GN-03097

|

not used

|

|

|

|

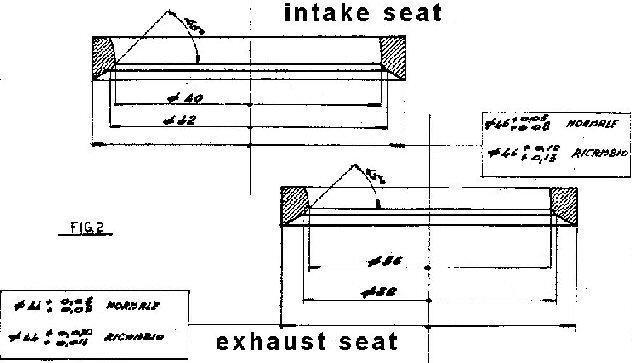

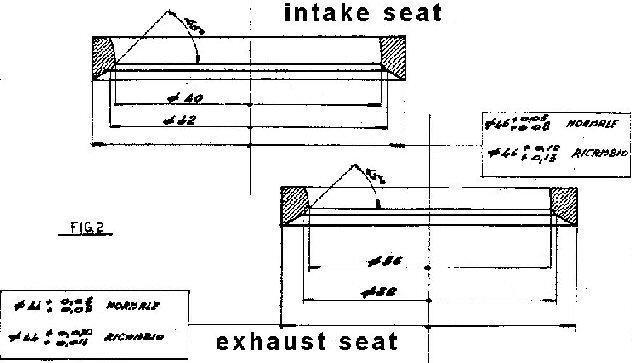

seat, intake

|

MD-00231

|

OEM berylium?

|

|

http://www.babcox.com/editorial/ar/eb40332.htm

|

|

seat, exhaust

|

MD-0232

|

OEM berylium?

|

|

http://www.babcox.com/editorial/ar/eb40332.htm

|

|

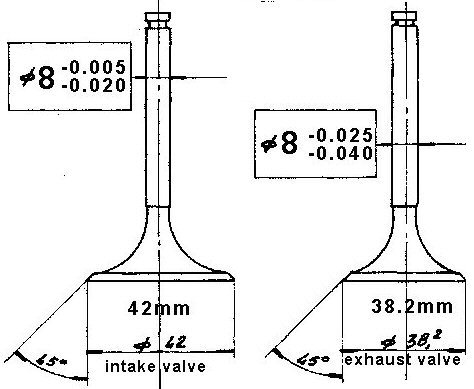

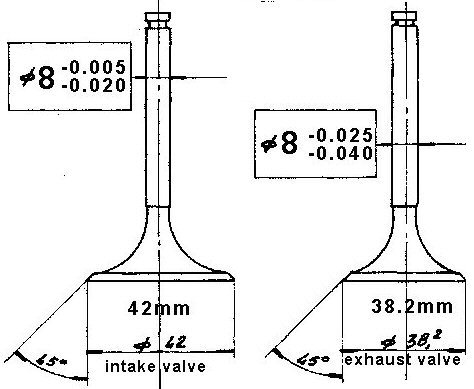

valve, intake

|

MD-01773

|

LIVIA 01773, 42mm,

8mm, 96.5mm

|

|

|

|

valve, exhaust

|

MD01774

|

LIVIA 01774, 38mm,

8mm, 95.6mm

|

|

|

|

o-ring,

|

GN-00464

|

|

|

|

|

o-ring,

|

GN-00473

|

|

|

|

|

o-ring,

|

GN-00407

|

|

|

|

|

o-ring

|

GN-00424

|

|

|

|

|

bearing, idler - 2ea

|

CRN-00433

|

K RIV -01A=6203

Car 053 ITALY 3 |

17 x 40 x 12 |

|

|

bearing, idler - 2ea

|

CAN-00478

|

double row needle

|

30 x 35 x 25.6

|

|

|

bearing, idler

MD06291/MD04381 - 4ea

2 piece roller brg, outer race/inner caged rollers and

race

|

GRN00433

|

outer - L

RIV 1DAG/22 ITALY 2

inner - L RIV 1DA/V22 ITALY 2

|

50 x 14

22 x 14

|

|

|

bearing, idler - 2ea

|

CSN-00429

|

K RIV -01A=6203

Car 053 ITALY 3

|

17 x 40 x 12

|

|

|

need info to complete table information

http://www.sivalves.com

http://www.raceenginedevelopment.com/pages/694927/index.htm

Fitting Valve guide seals to

early V12 Lamborghini engines - October 2007 - in progress, need

input

1) using stock valve guides, modify the

stock , installed guide to accept valve seals.

-heads off engine, valves out.

-8mm ID valve guide is used to pilot the cutter head

arbor.

-cutter head trims off the upper exposed OD of the valve

guide to create a surface for a valve seal.

|

|

2) using new design replacement valve

guides with seals fitted

-heads off engine , valves out

- remove old guides per factory proceedure.

- install new guides

|

|

possible helpful links for seals and

tools

|

http://www.qualcast.net/pdf/vssprog.pdf

|

valve seals

I recommend using stem

seals. If you plan to do a rebuild on the V12, you will be

replacing

the valve seats, valve guides, and probably, the valves

themselves. So

it is no big thing to have the valves made with a circular slot to

accomodate the seals. There are many out there that will work

fine. My

own engine (400 GT) has seals that were originally made for a BMW.

With

our engines, there are several quarts of oil in the cam chambers

at any

given time when the engine is running. The seals don't eliminate

oil in

the guides, but they do reduce it and likewise, they reduce the

amount

of oil that ends up in the combustion chamber, and therefore the

oil

consumption. Just my humble opinion, as they say. Other opinions

welcome! Jack

Good comment but not enough detail to let others follow

Yes I have used Valve Stem Seals

that

I had purchased from GTCP that are for a Ferrari, Had to

disassemble

the heads completely and set them up in my Mill and I purchased a

cutter for the 8mm valve stem guides and cut the guides for the

positive type seals. Sure eliminates the puffs of smoke on

restarts. I

would highly recommend doing them even if you have to seek out a

reputable machine shop. B/R Dave

Good comment but not enough detail to let others

follow

Valve Job

If the valves are the same

as a 400s countach, S I Industries has swirl polished

performance

valves that will work with minor machining needed. They are

a

Nissan/Datsun L-series valve 38mm head 8mm stem (exhaust), and

42mm

head 8mm stem (intake).The part #'s are 8002SG exhaust, and 8101E

intake. The stems needs to be shortened, and the intake head on

the SI

valve is a 43mm, your machinist will know what to do. I paid less

than

$10 a valve including 2nd day shipping. S I's # (805) 582-0085 -

Greg

Excellent follow up from Greg 10/05

Craig, The valves needed to be cut to length and a

retaining groove made, the price for the machine work came to

300,

$12.50 per valve. Eastco( the machine shop) had me purchase 1

new

intake, and 1 new exhaust valve(original) to take measurements

from. I

still have these valves if you are interested. The guides were a

VW

Gulf or Rabbit bronze with seal provision, better than the

original guide that with its angular top strips the oil from the

valve

stem, the original type of guides wear out quickly. 24 guides

$300,

rubber seals $54, replace guides $100, and the valve grind ran

$400.The

original seats were used. Hope this helps. I purchased valve

shims from

GT Carparts. BTW all my valve springs tested out in good cond. I

now

have about 2,000 miles on the engine rebuild, NO problems, and

I'm very

happy with the machine work, and the parts used, not to mention

the

savings from using quality parts that don't carry the expensive

Lamborghini name. Let me know if I can help in any other way.

Good

luck, Greg

Re: valve guide removal

First

mike up all your valve stems to see how true they are. If the

valve

stems are worn, replace the valves. Check the valve stem to

guide

clearance with a dial bore gauge. Most engines need .0015" to

.002"

stem to guide on the intake valves and .002" to .0025" on the

exhausts.

Any tighter and the valves are likely to sieze in the guides.

Much

looser and the valve job will be short lived. You might be

able to get away with knurling and reaming the old guides.

I don't like doing this because it is a short term fix. Better

off

doing it right the first time. If you do however want to go this

route,

K-Line tools has the tooling - knurling tool and reamers. I

think

Goodson sells their stuff. If you replace the seats, make

certain you use seats compatable with

unleaded gas. Same for the valves. The valves can be custom made

by

Ferrea, Rev, Manley, etc. No need to pay Ferrari prices. I

believe Nick

has another source he uses if you want to give him a

call. Steve

Excellent follow up from Steve

The method you descibed to remove the valve guides (predrilling

to relieve and then use an internal drift) is correct. Drilling

the guide ID will relieve the press fit enough to drive it out

with a

punch or air hammer without scoring the guide hole in the head.

What you need is a core drill. The drilling is best done

on a cylinder

head guide and seat machine but if you are careful, it can be

done by

hand.

Sunnen part # VGS156A

.312" pilot, .490" core drill diameter

1-800-772-2878

Goodson part # CCD-468A

.312" pilot .468" core drill diameter

1-800-533-8010

Do not heat the head to 300 degrees! You can warm the head a bit

but

the guides will come out at room temp once relieved. You

should

get guides .001" to .002" larger in diameter to replace the

guides you remove. You need no less than .002" press fit to keep

the

new guides in place. Steve

Head

work

Hello tech help, We heat aluminum heads in a turbo oven that

evenly

raises the

temperature of the head to 400 degrees and knock the guides out

with a

stepped punch on an air hamer. The guides come out with very

little

effort and virtually no damage to the heads. Valve seat

removal

depends on the situation but on a 308, for example,

we just mill two apposing notches in each seat so that the thin

wall in

the notched area collapses and the seats come right out with no

head

damage. We always install over-size seats for which the seat

pockets

have to be remachined so even if there was minor damage to the

metal it

would not matter. Same for new guides which we have custom made

for us.

Secure Installation of guides and seats depends on heating the

heads

and pre-chilling the inserted seats and guides but most important

is

extremely accurate machining, particularly of valve seat pockets,

to

ensure an interferance fit you can rely on. Robust and accurate

tooling

for driving in the chilled components is also critical. The head

has to

be re-heated frequently and properly supported. The inserted part

should be kept in a freezer untill just before use and hosed down

with

Minnesota Fast Freeze, or a similar product, after mounting it on

the

driving tool ready to install and then get it in there FAST before

it

heats up. After everything has cooled, the guides have to be

reamed to

fit the

valves and the seats have to be machined to line up with the

guides so

that the valves will seat correctly. properly done head work

is

not cheap for a reason - a lot of

pains-taking work and expensive, specialized tools, equipment and

parts. And you can't be annal enough if you want the job to last.

Wil

guide

removal

JBill Badurski- FCA Technical

Chairman, New member, Username: Badurski, Post Number: 2,

Registered:

06-2003RV, I've got to replace the valve guides on a pair of

Daytona

heads. Any tips or suggestions other than local heat and driving

them

out? JRV New member

Username: Jrv Post Number: 186 Registered: 05-2003

Posted on Saturday, July 26, 2003 - 08:09 am: Hi Bill, I was

taught to

drill the guide itself with a step drill 75% of the lenght of the

guide

(basically 90% boss depth) first leaving only about .20 -.30

thousanths

wall thickness left. Then heat, and press or drive out with a

drift.

The drift sits on the internal ledge left by the under drilling.

By

drilling all the center material out of the guides it releases the

compression fit and prevents the guide from expanding the boss on

it's

way out. It is important to drill striaght to prevent

going

into the boss material. The best type drill bits for this

operation have a stepped tip to aid in alignment and to keep

things

centered to avoid going thru the guide wall as the cut coes

deeper.

It's nice to start on the seat side so the guide is removed out

the way

they go in. But sometimes on well worn guides the drill bit won't

center well enogh for the long cut. If you need a better

explanation of the procedure we can talk on the phone. Regards,

JRV

Valve Seat Installation Procedures

by Larry Carley, Technical

Editor

lcarley@babcox.com

Valve seats are an extremely

important

part of a cylinder head because the seats cool and seal the

valves.

They also support the valve when it closes, which affects both

valvetrain geometry and valve lash. If a seat is damaged,

cracked,

loose, receded or too badly worn to be recut or reground, it can

cause

a variety of problems: loss of compression, valve burning, valve

failure, valvetrain wear and breakage, even head and valve

damage if

the seat comes loose.

For that reason, replacing valve

seats

is often necessary when reconditioning aluminum or cast iron

cylinder

heads. Another reason to replace a seat is if a valve has broken

because the seat is not concentric with the guide. Misalignment

between

the seat and guide causes the valve stem to flex every time the

valve

closes. Eventually, this flexing leads to metal fatigue and

valve

failure. When this happens, the counterbore must be remachined

(if the

head is salvageable) to realign the seat with the guide.

New seats may also be required if a

cylinder head has been straightened or welded, if there’s any

evidence

of corrosion around the outside diameter of a valve seat, or if

the

engine is being converted to run on a dry fuel such as propane

(LPG) or

natural gas.

Integral seats in cast iron heads are

no

less important even though the seats are part of the head

itself. An

integral seat may have to be cut out and replaced with a new

insert if

the seat has receded, is badly worn or damaged.

How Often?

Some experts say when late model aluminum heads are

reconditioned

the valve seats should always be replaced to maintain correct

valvetrain geometry. This applies to overhead cam engines as

well as

pushrod engines. It’s expensive but is usually necessary to

restore

proper installed valve height and valvetrain geometry.

Rick Emert, product and technical

services manager for SB International, says most valve seat

failures

(more than 50 percent) are due to one of two things:

misapplication

(wrong valve and seat combination) or valvetrain "mismotion"

(incorrect

valvetrain geometry or lack of seat/guide concentricity). He

also

explains that preignition causes a lot of seat failures, too.

"When seats get too hot, microwelding

occurs between the valves and seats. The valves are harder than

the

seats so microscopic particles of metal from the seats stick to

the

valves," says Emert. "When the engine cools, these particles are

then

washed into the exhaust. This causes rapid recession of the

seats and

is most common in dry fuel (LPG or natural gas) engines."

Emert said another reason for

replacing

seats in some late model heads is because the OEM powder metal

seats

become too hard to machine. Many late model gasoline engines

with

aluminum heads from Ford, GM, Chrysler and many imports are

factory-equipped with sintered powder metal seats. Powder metal

seats

are used because they are harder and more durable.

Powder metal seats combine various

materials to achieve special properties. Many powder metal

formulas

work-harden as the engine runs. A new powder metal seat that has

a

hardness of RC 25 when it is first installed will develop a

hardness of

RC 40 to 50 after several thousand miles. Seats that hard are

difficult

to refinish by cutting, so one alternative to grinding is

replacing the

old seats with new powder metal or alloy seats.

Emert says his company recommends

alloy

seats for most applications because they are easier to machine.

"We

have eight different alloys in our product line, and each one is

engineered for a specific type of application." His company’s

two most

popular alloys are "Cast XB" (an iron-based alloy), and

"N-Series" (a

nickel-based alloy). SB International also has powder metal

seats for

those who want to install the same kind of seats as original

equipment,

Emert says.

"But we don’t recommend installing

powder metal seats in diesel engines because powder metal seats

can’t

take the heat and compression in this kind of application. They

may

shatter," says Emert.

Other valve seat manufacturers offer

a

variety of different alloys for valve seat inserts, as well,

including

various powder metal formulas. But powder metal has been slow to

catch

on in the aftermarket. Although engine rebuilders are seeing

more late

model heads, many still prefer to use alloy inserts.

However, Bill Dolak of Dura-Bond says

traditional cast iron seats won’t hold up well in late model

engines.

He recommends one of two different alloy seats depending on the

application, either the "30000 Gold Series" valve seat inserts

made of

finely dispersed tungsten carbide in a matrix of tempered tool

steel

and alloy iron particles, or his company’s "70000 Diamond

Series"

inserts which use a higher temperature mix of tool steel and

tungsten

carbide. He says the 30000 Gold Series seats are easily machined

and

offer good wear and heat resistance for naturally aspirated and

turbocharged engines. For high performance, heavy-duty and dry

fuel

applications he recommends the higher temperature 70000 Diamond

Series

inserts.

Dale McKitterick of Precision Engine

Parts clarifies what alloys are appropriate for which

applications. His

company offers high chrome alloy seats (which are good for

unleaded

gasoline engines in most passenger car and light truck

applications),

nickel alloy seats and M2 tool steel alloy seats (for severe

duty, high

temperature applications), ductile iron seats (popular with many

race

engine builders) and beryllium/copper seats (used mostly in

megabuck

high end racing engines). McKitterick says he also has powder

metal

seats, but only a few customers have asked for them.

Qualcast, Tucker Valve Seats, Martin

Wells and others all offer a variety of different alloy seats

for

various types of engine applications. The important point here

is to

choose a replacement seat that is right for the application.

Higher

load, higher temperature applications require harder seats.

Follow the

recommendations of the valve seat insert suppliers because they

know

what works best in each type of application.

Cast iron inserts are still used for

light duty intake valve applications but should never be used on

the

exhaust side. The metal is just too soft to withstand the

operating

temperatures. For exhaust valves, a hard insert made of high

chrome

stainless steel, high nickel alloy or a heat resistant alloy

must be

used. Stellite inserts, which are made of a nonmagnetic cobalt

alloy

and are the hardest inserts available, are recommended for the

exhaust

valves in heavy-duty, high temperature engines and those that

burn dry

fuels such as propane or natural gas.

Tom Tucker of Tucker Valve Seat,

says 440 stainless steel seats or Silicone XB (an iron seat with

18

percent chrome) are the most popular aftermarket seat materials

today.

But he also stressed the importance of choosing a seat that’s

designed

for a specific application.

"We have a tool steel tungsten

carbide

material for natural gas applications that holds up especially

well. We

also have an ‘E’ series material that provides superior hot

hardness

but is not as hard or abrasive as #3 Stellite."

Roger Klump of Martin Wells says his

company has been selling its Well-Tite alloy for more than 30

years and

he’s never seen a failure with the product. "It has the same

wear

characteristics as a 52 RC Stellite-type of product but with a

hardness

of only RC 35 to 37," explains Klump. "The Well-Tite alloy

contains 42

percent nickel, which provides good heat transfer and valve

cooling. It

also contains 10 to 12 percent chrome for oxidation resistance,

and 7

percent moly for toughness."

Preliminary Steps

Seats should not be replaced until the head has been

thoroughly

cleaned and inspected. This includes checking for cracks

(especially

around and near the valve seats) and checking the deck surface

and cam

bore for straightness. Any welding and/or straightening that may

be

needed must be done before remachining the valve seats or

installing

new inserts.

Also, the valve guides should be

replaced or reconditioned before the seats are machined.

Concentricity

between the seat and guide is absolutely essential for a proper

alignment, good compression and long term valve durability.

The cylinder head must be

dimensionally

and geometrically within specifications before seat counterbores

are

machined. That includes cylinder head thickness, valve guide

clearances, concentricity and perpendicularity. There should be

no

warping, twisting or any type of misalignment anywhere in the

head.

Seat Removal

The first step in seat replacement is removing the old

seats. A

variety of methods can be used to remove valve seat inserts from

aluminum heads. Putting the head in a cleaning oven is sometimes

used

to loosen the seats enough to where they may fall out. Knowing

the

secret password necessary to keep good seats in place while

allowing

the damaged heads to release is critical (of course, there is no

password). Using an oven in this way is a lengthy process that

offers

no real "predictability" regarding seat loosening.

Another method that does not involve

heat is to use a cutter slightly smaller than the outside

diameter of

the existing valve seat insert to cut away most of the old

insert (this

works on softer alloy seats but not very well on powder metal

seats).

Stop cutting when the old seat begins to rotate in the head.

What

remains of the old seat can now be easily removed.

Another method of cutting out a seat

is

to use a die grinder to slit and weaken the seat. Just be

careful not

to cut all the way through the seat and into the counterbore.

Prying out valve seats also works if

there is enough of a lip under the inside edge of the seat, but

this

technique also risks damaging the counterbore if not done

carefully.

To remove hard seats, arc weld a bead

all the way around on the seat. As the bead cools, it will

shrink and

loosen the seat. For more information on this procedure, see the

March

issue of Engine Builder, page 28, "The Whys and Hows of Welding

Aluminum."

Another trick is to place a valve

that’s

somewhat smaller than the seat in the head and weld the valve to

the

seat. The valve stem can then be used like a driver to push out

the

seat.

Once the inserts are out, check for

cracks or erosion damage under the seats in the counterbores – a

common

problem on many aluminum heads. If cracked or eroded, the metal

can be

rebuilt by TIG (tungsten inert gas) welding, and remachining the

head

to a new seat.

Cutting Counterbores

Many experts recommend recutting the counterbores to accept

new

oversized seats. Some engine builders will install new

standard-sized

inserts in the existing counterbores. It works on some large

cast iron

cylinder heads with thick walls, but it’s risky on most

automotive

applications. The recommended approach is to remachine the

counterbores

to accept oversized inserts. This allows you to control the

interference fit between the seat and head so the seats don’t

come

loose.

Recutting the counterbore also allows

you to control runout in the counterbore and concentricity with

the

valve guide. The counterbores must be smooth, round, have flat

bottoms

and be centered to their valve guides for proper alignment

and good heat transfer between the seat and head. The final

dimensions

of the counterbores must be within .0005˝ for the proper fit.

If a counterbore is too rough,

distorted or out of round, it won’t make good metal-to-metal

contact

with the seat. It can also distort the seat. This will reduce

heat flow

from the seat to the head and make the valve run hot. That you

don’t

want because it leads to valve burning and warranty problems

down the

road.

If you’re replacing an integral seat

in a cast iron head (and the cylinder

head has enough thickness to accept a new seat), the counterbore

should

be cut to a diameter approximately .100˝ larger than the valve

head

diameter. The inside diameter of the replacement seat will

typically be

about .100˝ smaller than the valve head diameter and

require a depth of about .188˝ to .250˝ depending on the

application.

Accurate

cuts also require proper fixturing. Keep your tooling setup as

"short

and tight" as possible to assure maximum rigidity. The less

deflection

in the tooling, the more accurate the dimensions of the cut and

the

greater the concentricity of the counterbore.

Be careful not to distort or put a

twist into the head when clamping it to a fixed rail holding

fixture.

You’ll get the most accurate cut with

correct size pilots (which must be straight), and using the

correct

spindle speeds and feeds. Machining recommendations vary

depending on

the type of equipment and tooling used, but Dura-Bond recommends

using

cutting oil and a spindle speed of 400 to 600 rpm when cutting

valve

seat counterbores in aluminum heads. When cutting cast iron

heads,

Dura-Bond recommends using no lubrication and a slower cutting

speed of

100 to 250 rpm.

Something else to keep in mind when

cutting counterbores is that the seats for many late model heads

don’t

go by fractional sizes anymore. Seat sizes can vary considerably

so

using a fixed size cutter is not the best choice. An adjustable

cutter

will provide the flexibility you need to properly size the

counterbores.

Interference?

The recommended amount of interference between the valve

seat

insert and head may vary depending on the size of the insert,

the type

of insert (alloy or powder metal) and type of head (cast iron or

aluminum). The best advice is to use the amount of interference

recommended by the OEM engine manufacturer.

Too much interference runs the

risk of cracking the head while too little interference

increases the

risk of the seat coming loose or falling out. One of the leading

causes

of seats coming loose, however, is not the amount of

interference

between the seat and head but elevated operating temperatures.

Anything

that causes the exhaust valve to run hot may also cause the seat

to

loosen.

Philip Carrasco at Tucker says seats may

require anywhere from .002˝ to .010˝ of interference depending

on the

application and the roughness of the surface in the counterbore.

For

aluminum heads, an interference fit of .005˝ to .007 ˝ is

commonly

used. For cast iron heads, .003˝ to .005˝ is about right.

Martin Wells’ Roger Klump says he

recommends an interference

fit of .005˝ to .006˝ for everything, aluminum and cast iron.

Rick

Emert of SB International says he tells his customers to use

.005˝

press fit when installing seats in cast iron heads, and .007˝

minimum

in aluminum heads regardless of what type

of valve seat inserts they are installing. "We do not recommend

using

any type of locking fluid, staking or peening when installing

seats.

You should be able to put a concentric seat into a concentric

hole with

the right amount of interference and have it stay there," says

Emert.

Carrasco, on the other hand, says a

lot

of engine builders have had success using a locking fluid. "They

tell

me it helps fill any voids between the seat and head for

improved heat

transfer and valve cooling. You don’t see many production engine

rebuilders doing this but you do see smaller shops doing it,"

said

Carrasco.

Seat Installation

Installing the new seats once the counterbores have been cut

is a

fairly simple procedure. A piloted driver is used to push the

seat into

position. Many aftermarket seats have a bevel or radius on the

outside

lower edge to make installation easier. Make sure this side

faces down

when installing the seat.

Some engine builders preheat the head

or

chill the inserts in a freezer or with nitrogen prior to

installing

them to make the job easier. Others say this should not be

necessary if

you use the normal amount of interference fit. Even so, it’s

another

trick that may come in handy on a problem head or application

that

requires something out of the ordinary.

Seat Finishing

After the seats have been installed, they can be finished as

required. The guides must be reconditioned or replaced before

doing

this, however, because all seat work is done by centering off

the

guides.

Seats should be as concentric

as possible for a tight compression seal and proper valve

cooling. The

rounder the seat, the better. Seat runout should not exceed

.001˝ per

inch of seat diameter. Some shops aim for .0005˝ or less of

runout.

The best way to check concentricity is with a runout gauge.

Pulling

vacuum on the valve port with the valve in place is another

method for

checking the mating of the seat and valve. But the ability to

hold

vacuum is no guarantee of concentricity. Both methods should be

used to

check the quality of your work.

Seat width is also important for good

heat transfer, proper sealing and long valve life. If the seat

is too

narrow, wear resistance and heat transfer can suffer. And if the

seat

is too wide, there may not be enough pressure to provide a tight

seal.

A wide seat also tends to trap deposits that can hold the valve

off its

seat. This too, can reduce heat transfer as well as compression.

As a

rule of thumb, the ideal seat width for intake valves is usually

around

1/16˝. For exhaust valves, it’s 3/32˝ – or whatever the manufacturer specifies.

The point at which the valve and seat

mate is also important. If the area of contact is too high on

the valve

face (too close to the margin), the valve may be sunken into the

head.

This increases installed height, upsets valvetrain geometry and

restricts free breathing. If the area of contact is too low on

the face

(too far from the margin), the valve will ride too high on the

seat. As

the engine warms up and the valve expands, the contact point

moves down

the valve face away from the margin. The valve may lose partial

contact

with the seat causing it to lose compression and run hot.

Ideally, the valve should contact the

seat about one third of the way down the valve face (about 1/32˝ from the margin) so there

is about 1/64˝ of overhang between the margin and top of the

seat. EB

|

BACK TO

BASICS – Valve Seats

The most critical sealing

surface in

the valve train assembly is between the face of the valve

and its seat

in the cylinder head when the valve is closed. Leakage

between these

surfaces reduces the engine’s compression and power and

can lead to

valve burning. To ensure proper seating of the valve, the

valve seat

must be:

- Correct width

- Correct location on the

valve face

- Concentric with the guide (less than .002˝ runout).

The

ideal seat width for automotive engines is 1/16˝ for

intake valves and

3/32˝ for exhaust valves. Maintaining this width is

important to ensure

proper sealing and heat transfer. However, when an existing seat is refinished to make it

smooth and concentric, it also becomes wider. Wide seats

cause the following problems:

- Seating pressure drops as

seat width increases.

- Less force is available to

crush carbon particles that stick to the seats.

- Valves run cooler,

allowing deposits to build up on them.

The

seat should contact the valve face 1/32˝ from the margin

of the valve.

When the engine reaches operating temperature, the valve

expands

slightly more than the seat. This moves the contact area

down the valve face.

Seats that might contact the valve face too low might

lose partial contact at normal operating temperatures.

Like valve guides, there are

two types

of valve seats – integral and insert. Integral seats are

part of the

casting. Insert seats are pressed into the head and are

always used in

aluminum cylinder heads. Most pre-1978 integral seats

are soft cast

iron. After 1978, most manufacturers began to produce

cylinder heads

with induction hardened cast-iron seats able to

withstand the higher

heat of exhaust applications. Insert seats are added to

the cylinder

head after casting, or as replacements for worn integral

seats.

from the book:

"Complete

Automotive Engine Rebuilding and Parts Machining"

|

Now for some added

confusion/clarification originating from Down-Under !!!! :-))From my

Italian Espada Manual, there is a section on valve springs, which I

have hopefully translated correctly.There are 2 part numbers given

for

both inner and outer springs and 2 different sets of figures - it

appears that there are differing springs for older and later Espada

motors. On the parts listings

I have, the 2 numbers appear on different drawings - the second

number in each case seems to be from the later engines

Outer Valve Springs

Part Number 1202083

Uncompressed length - 49mm

Valve Closed length - 35mm at 20kg +/- 1kg

Valve Open length - 28mm at 28.6kg

Part Number 1213133

Uncompressed Length - 59mm +/- 1.2mm

Valve Closed Length - 36mm at 36.5kg +/- 1.5kg

Valve Open Length - 26.5mm at 51.6kg +/- 2kg

Inner Valve Springs

Part Number 1201020

Uncompressed length - 49.8mm

Valve Closed length - 37mm at 25kg +/- 1kg

Valve Open length - 26.5mm at 45.6kg

Part Number 1213132

Uncompressed Length - 48mm +/- 1mm

Valve Closed Length - 36mm at 26.2kg +/- 1kg

Valve Open Length - 26.5mm at 47kg +/- 1.8kg

These are direct copies of the values – why some have tolerance

values,

and other don’t, I don’t know. Likewise some of the figures seem a

bit

odd – lengths especially – they are copied accurately, again I don’t

know why….

There is a statement regarding the valve spring numbers which I

can't

understand - can somebody else translate for me please. This

concerns

the outer springs

rif.lamborghini 1202083 fino alla 1150a vettura, rif.lamborghini

1213133 dalla 1151a vettura

Likewise there is the same statement using the two part numbers for

the inner springs

rif.lamborghini 1201020 fino alla 1150a vettura,rif.lamborghini

1213132 dalla 1151a vettura

Given that there are two different spring part numbers and

corresponding values for the Espada, I would tend to believe that

there

would be other part numbers and values for the higher power engines,

especially the Miura, LP400 and LP400S. Likewise the older engines

in

the GT350 and GT400 which have lower power engines may have other

part

numbers and values. Knowing the variations that occur in the cars, I

can't believe that Lamborghini would have all the valve springs of a

standard size and value.

John - April 08,05

the following is an

interesting Q&A at FerrariChat.com

valve guide removal and seats

Hello tech help,

i am in need of some exacting help on locating a a supplier of the

correct type drill bits for removing valve guides. My guides are 8mm

bore (but slightly worn), the OD of the guides are 13mm. Aluminum

heads

of course with bronze style 60's era valve guides. I understand a

"pilot" drill bit with an 8mm guide is what i need to take out the

bulk

of these guides prior to knocking them out. Maybe 12mm bit.

I have been told the technique is to drill away 80% of the internal

bronze material, then using a custom punch to fit this new internal

"step", heat the head to say 275F and punch them out.

Who would supply a piloted drill bit? any help would be wonderful.

thanks

Craig

fatbillybob says - NO

NO NO you are getting the bum steer! DIY'ER at home you heat in

pizza

oven to 300 degrees F. and drive out with an air hammer made on a

lathe

to the exact size of the valve guide. There is no drilling needed.

If

you are just our of spec sometimes you can leave the guide and knurl

them at a machine shop and that is just enough to prevent oil

passage.

Often all you really need the 1st time is new oil seals. Ferraris

like

355's and 308's have been known to eat these seals but yet have

valves

and guides in spec.. You will need a machine shop to replace the

guides, square them to the head, measure run out to the valve seat,

angkle the seats, cc the head mill the deck. Therefore why not let

them

remove the guides too if you don't have the right tools? It is very

important to do these little details properly. Forecxample if you

deck

the head too much to increase the CR you have to shim the cams to

maintain the timing relation. Are you ready for these kinds of

things?

Fred2 says -

The instructions that you are talking about are the same that I was

given for removing the guides from an aluminum alfa head. The reason

for drilling the guides, was that the punch would act on the far

side

of the guide, and "Pull" it out. If you hammer on the side in the

port,

you may mushroom the guide, and

wear the cylinder head. This would result in a sloppy fit for the

new

guide. If you decide to drill the guide, the hole that is in there

will

act as your pilot. You would have to work real hard to NOT drill the

hole concentric. If you split the difference between the OD and the

ID,

you should be OK

on Drill diameter. Plan ahead, and first find a drift with the

diameter

to match the drill you will be using.

P400 says -thanks

fatbillybob and fred2, i understand that this work is fairly simple

for

a DIY project. i am told that Neway tools may have all the step

drills,

step drifts, valve seat cutter tooling, etc. Are you aware of any

other

tool suppliers?

Is there any experience to guide me in purchasing guides,

seats and

valves from a high quality supplier......maybe SI Valve? or Manley

Valve? or ? you folks are just great for help on this thank you

Craig

MattMorgan"Kermit" says - Or

if you want to try a diffferent way yet, Use a 3/8" nc "gun tap"

(they

push the chips out ahead of the tap,with an extension long enought

to

reach most of he guide, the STD 2 valve bore is close to the drill

size

for the tap as is.A variable speed drill is good here Tap the guide

3/4th of the way down from the top (let the tap follow the hole, and

it

will center every time). out a threaded rod into the guide, add a

short

block that has a center hole at the base long enough,. and wide

enough

for the guide,. put a nut and washer on top, and either crank it

with a

ratchet, or better yet, an air ratchet, and it pulls them easily.

The

tapping removes enough to release, and the threads pull fro the

inside,

a better way that hammering them, as they cannot mushroom.

HTH. Kermit

With an air ratchet, I have done both heads in under a half hour

with no galling, etc

Fatbillybob says -

IMO you guys are doing way too much work. The guides are press fit

with

heat expasion. When you heat the head those soft silicon bronze

guides

drift right out with a simple drift and hammer. They never mushroom

and

you never gall the head unless you are doing this cold. Some

mechanics

do this cold and have no problem. Even heat is the preferred method.

I

have done this cold and with a torch when oven was not available.

The

right tool is what you need. Drilling just weakens the guide but

does

not change its dimension or press fit. If you drill it enough to

severely weaken it you can 1) hit the casting if you do not stay

perfectly concentric 2) now have such a thin guide that it is

difficult

to drift out. That is why the tool to do this job is called a drift

punch and is matched to the land and inner diameter of the valve

guide.

90% of car makers have a special tool just for their application.

Some

stuff can be done crudely in your garage but you need precise tools

to

make sure the guide is in perfectly square and with proepr runout

with

the valve on the seat etc.. This is much more precision oriented

than

say ridge reaming a cylinder in the garage. But you can get 90% of

the

way there by just slapping the parts in and hoping that manufactuer

tolerances are close enough for a decent fit and therfore decent

function. So yeah you could do it with Neway tools and a clean

garage.

tomoshea says - I

have spoken to many specialist Ferrari engine rebuilders as I have

just

completed a total top and bottom end rebuild on a 308 engine.

Interesting facts.

1) The amount of metal surrounding the inlet and exhaust valve

guides

is not the same on the 308 this casues alignment problems when you

replace the guides!!!!, they "kink" when the heads cool down.

2) Ferrari had problems using already drilled guides in the factory

and

getting the valves to line up with the centre of the the hole for

the

seats.

3) To sort this out Ferrari fit solid guides in the 308 engine then

bored out the core so they could ensure alignment with the valve

seat.

Now if you air jack or push out the guides that are in place (even

with

the heads heated up) you will strip small amounts of aluminium off

the

head and I can guarantee you from personal experience that you will

have problems aligning the the new guides/ valaves an seats.

All the guys that do this for a living have told me that you need to

drill out the guides in place to almost the full diameter and then

use

a drift to "push" out what ever thin amount of metal is left (this

should be done with the head hot)

This makes rebuild considerably easier and will save you time in the

long run.

However if you were going to replace the seats ignore all of the

above.

Regardless always heat the heads and then air cool the guides before

you try to remove them.

Don't do it cold one professional told me of a very nasty expensive

experience he had when he did this!

fatbillybob says of tomoshea

above - Urban legend to justify those high Ferrari engine rebuild

prices. I

have never seen this and rebuilt perhaps 4 Ferrari engines in my

time,

myself, with proepr tools , line bored cam journals the whole bit.

Actually, these casting are surprisingly good adn you could do this

in

your garage with very few tools and get 90% close for a decent

running

car.

dbcooper says -We've

done many,many heads where we air hammered the guides out cold and

have

had 0 problems/mistakes. whether this method is correct or not is

reflected in the numbers if ya ask me.

fatbillybob says of dbcooper

above - O.K. listen up folks here is a guy who speaks the same truth

I speak.

I've done 4 engines myself from cradle to grave and many more

indivdual

heads. This echos my experience too but I have a mixture of doing

this

job with all the best tools and with no tools.

You must be lucky! I have rebuilt one top end and had up to 5 tho

out on some of the new

guides (not a major issue but did require cutting the seats).

Superformance, QV, Nick Cartwright and others in the UK, who by the

way

was never going to benefit from the advice they gave me, as I was

doing

the work myself with a local machine shop in Ireland advised me that

based on all there years of experience they always drill out and

then

punch, for the reason quoted above.

Horses for courses!, you might have touch that others don't have

when it comes to getting stuborn guides out of Ferrari heads.

By the way my engine was a 79 Ferrari and the castings were not the

best finished heads I had ever seen (understatement).

Artvonne says - Interesting

subject, as I need to contemplate my direction on this as well. What

are others thoughts on some of the old industry fixes, such as:

Knurling the guide, Sleeving the guide

I have always been of the opinion that if the guide was worn it

should realistically be replaced, that those two "options" were

considered bandaids. However, I also seem to recall that many

performance shops would sleeve the guides with a better bushing

material that allowed the valve to keep sliding and stay lubricated

at

high speed and temperature. Also that with real tight guides, some

would not run a seal, but allow the oil to go were it wanted, with

only

the clearance to hold it back, and thus the name "Valvoline" was

born.

The proverbial smoking Italian car that always needed that special

tuneup to clear itself after long periods of slow running.

P400 says -Thanks for the

help,

i went to Neway tool site -

http://www.newaymfg.com/frame.htm

they show the valve seat cutting tools and the valve refacer tools,

but not showing guide step drills or drifts.

my question for the folks predrilling guides -

what company or resource do you use for drills and drifts?

i would see the drill having a 8mm guide to follow the existing hole

and then step up to 11.5 or 12mm.

who provides these?

any help on this is great. the existing guide material is bronze.

Craig

fatbillybob says of tool

search above - I f you can't find it make it. You can take an

existing air hammer tool

and chuck it in a lathe and spin it down. If you don't have a lathe

you

can find a tool that is less than the overall diameter and has the

pointed tapered end. Those air hammer bits are very standard. Then

you

break out your file and file a land in the tapered point to match

the

land of the guide 11mm? and around you file until about 8mm

diameter,

you do not need to be precise here, and there you go. Then you heat

the

tool red hot with a torch and quench it in oil..voila!

Artvonne says - Well,

there must be some reason all the aircraft mechanics heat all the

jugs

up with a rosebud torch before removing or installing guides. And it

matters not who made the engine, what model it is, or year, or size.

I

am able to recognise that maybe its done that way simply because

thats

the way its always been done, and there may not be a valid reason,

but

then again.....

Its funny, but not real funny, that most cars for example can last

for years and run well past 100K miles in original condition, and

then

it gets cylinder head work, and some new valve seats. Next thing you

know, you see this engine that dropped a seat, and the damage can be

absolutley amazing. I guess the thing to keep in mind, is that a guy

dont have to work on Ferrari's to know mechanics, and that just

because

someone calls themselves a mechanic, doesnt mean you want thier help

fixing your John Deere. Its almost like for every good mechanic

there

are about 10 others who can screw up things so awful you were

probably

better off if they never touched it. I honestly cannot count the

times

I've taken parts to an aircraft mechainc, simply because I couldnt

find

anyone else qualified.

I would also agree here, that at least with this 308 motor, I can

see nothing so exotic that a good general mechanic shouldnt be able

to

work on it. And simply looking at the V-12's and at parts books they

seem equally the same. But you say that F word and either everyone

runs

for cover, or they smile nice and ask for vast volumes of your

money.

To wit, I was quoted over $2K per head for a standard valve job by a

shop in the twin cities. They had done some work on a 355 and now

thought thier crap didnt stink.

Mark says -

My previous occupation was a tool and die maker, I have a lot of

experience driving punches and bushings in and out and counterboring

holes. I agree that "drilling-out" the guide would relieve a lot of

pressure from the interference fit. If I were going to drill the

guides-out I would probably use a counterbore and a regular hand

drill.

Keep in mind, brass and bronze have some bad machining

characteristics

for drilling in that a sharp cutter can catch and act like a tap and

the cutter will rapidly and uncontrollably be pulled right thru the

material. With a hand drill it should be easy to control, but in a

milling machine with a high chip load it can pull the part out of a

vise and cause a lot of damage. In most cases when drilling bronze,

people take a stone and lightly dull the edge of the cutter.

As for heating the head, I'm not sure I would recommend doing this

unless the guide was going to be cooled just prior to removal. The

best

way may be to heat the assembly and then "squirt" liquid nitrogen

into

the guide (to shrink it) and use a drift to knock it out. The reason

that I would probably not heat the head and drive the guide out is

because I think bronze has either a similar or higher coefficient of

expansion then aluminum; therefore heating would likely increase the

interference, not improve it. However, if the assembly was heated

and

then the guide was cooled it would come out most easily. Even cold

water squirted thru the guide in a heated head would help.

On motorcycles, I have sqirted them with penetrating oil then

knocked

them out cold. For installation, I would reccomend freezing the new

guides and install into an oven heated heated head--they slip

right-in.

Prior to putting the guides back in it is important to clean and

hone

the hole out. They have some of those hones with the balls of stones

on

--these would work great. You will not remove hardly any material --

it

would take some serious effort to remove even .0002”. A couple of

light

passes with a hone will refinish the hole and will work wonders to

really facilitate installation.

As far as locating counterbores, a machine shop supply firm would

have them. Do a search here for counterbore or spotface http://www.mcmaster.com/

check pages 2319 and 2320. There is a place in Paramount, Ca, (Cal

Aero) that randomly sells these interchangeable cutters used by the

pound. I have a few, in fact I have one that looks like 3015a22, but

has about a 1/16 radii in the corners. Send me an email and I’ll

send

it to you, you can try it/use it for free. I only have a ¼

inch pilot,

but this could be “shimmed-up” to .3125” with a piece of brass tube

from a hobby store.

Keep us posted on your progress. Mark

P400 says -thanks for all the

input!

i have found a valuable pdf catalog of possible interest to all in

this valve work mode.

http://www.pirate4x4.com/tech/billav...ne%20tools.pdf

quite a few tools for all types of work are available

core drills, knurling or spiraling, all types of valve seat

equipment, etc

i will need time to digest this catalog.

my OEM stems look within tolerance.

this is a vintage car for me to zoom around in, but i am not racing

for championship points. nor is this a commuter car.

I am considering -

knurling guides

having valves professionally refaced

having seats professionally refreshed

reassemble

this may fit my 200 miles a year plan for this V12 car.

however i am not sure it would not be best to renew all, replace

seats and valves with modern gasoline compatible materials.

If any of you wonderful folks have purchased seats, valves and

guides recently, what vendors and materials did you use?

Manley? Ferrea? SI? Rev? or others?

any help would be fantastic and probably help all involved

Craig

Atrvonne says - Well,

we got the guides covered, now what about this guys other questions,

like were has anyone gotten thier parts from, and how do you guys

remove and install seats? None of us, especially me, want any seats

falling out.

dbcooper says - out cold. in

hot - we

pounded them out cold and heated the heads with a propane coleman

stove

to heat heads before guide install.sorry for not pointing this out

before.out cold no problem with air hammer.We also just bought

storage

jug/thermos to super cool with liquid nitrogen for liners and guess

will use for guides too?

wildegroot says - We heat

aluminum heads in a turbo oven that evenly raises the

temperature of the head to 400 degrees and knock the guides out with

a

stepped punch on an air hamer. The guides come out with very little

effort and virtually no damage to the heads.

Valve seat removal depends on the situation but on a 308, for

example,

we just mill two apposing notches in each seat so that the thin wall

in

the notched area collapses and the seats come right out with no head

damage. We always install over-size seats for which the seat pockets

have to be remachined so even if there was minor damage to the metal

it

would not matter. Same for new guides which we have custom made for

us.

Secure Installation of guides and seats depends on heating the heads

and pre-chilling the inserted seats and guides but most important is

extremely accurate machining, particularly of valve seat pockets, to

ensure an interferance fit you can rely on. Robust and accurate

tooling

for driving in the chilled components is also critical. The head has

to

be re-heated frequently and properly supported. The inserted part

should be kept in a freezer untill just before use and hosed down

with

Minnesota Fast Freeze, or a similar product, after mounting it on

the

driving tool ready to install and then get it in there FAST before

it

heats up.

After everything has cooled, the guides have to be reamed to fit the

valves and the seats have to be machined to line up with the guides

so

that the valves will seat correctly.

properly done head work is not cheap for a reason - a lot of

pains-taking work and expensive, specialized tools, equipment and

parts. And you can't be annal enough if you want the job to

last. Wil

Steve says -The method you

descibed to remove the valve guides is correct. Drilling

the guide ID will relieve the press fit enough to drive it out with

a

punch or air hammer without scoring the guide hole in the head.

What you need is a core drill. The drilling is best done on a

cylinder

head guide and seat machine but if you are careful, it can be done

by

hand.

Sunnen part # VGS156A

.312" pilot, .490" core drill diameter

1-800-772-2878

Goodson part # CCD-468A

.312" pilot .468" core drill diameter

1-800-533-8010

Do not heat the head to 300 degrees! You can warm the head a bit but

the guides will come out at room temp once relieved.

You should get guides .001" to .002" larger in diameter to replace

the

guides you remove. You need no less than .002" press fit to keep the

new guides in place.

Thank you Steve, this is

giving me the lead i need to pursue this job to completion. i

downloaded a Goodson pdf catalog.

http://www.pirate4x4.com/tech/billav...ne%20tools.pdf

i now find i have two (logical) options -

1) remove and replace all pieces. - guides, seats, valves, shims

2) refinish and reinstall oem pieces. - knurl guides, recut seats,

reface valves.

This 1968 V12 4 cam P400 Miura engine with bronze guides and seats

will

not get driven much. Everything looks nice, little wobble felt in

guides, valves showing a radius seat , maybe this is called cupping?

i am thinking of knurling guides, recutting seats with Neway, have

valves professionally machine shop to reface at 45 degrees. now all

sits lower in hole, and so material needs to come off stem face? and

the amount is based on valve shim sizes logical to go in this

application?

thank you if you have time for this.

Steve says - First mike up all

your valve stems to see how true they are. If the

valve stems are worn, replace the valves. Check the valve stem to

guide

clearance with a dial bore gauge. Most engines need .0015" to .002"

stem to guide on the intake valves and .002" to .0025" on the

exhausts.

Any tighter and the valves are likely to sieze in the guides. Much

looser and the valve job will be short lived.

You might be able to get away with knurling and reaming the old

guides.

I don't like doing this because it is a short term fix. Better off

doing it right the first time. If you do however want to go this

route,

K-Line tools has the tooling - knurling tool and reamers. I think

Goodson sells their stuff.

If you replace the seats, make certain you use seats compatable with

unleaded gas. Same for the valves. The valves can be custom made by

Ferrea, Rev, Manley, etc. No need to pay Ferrari prices. I believe

Nick

has another source he uses if you want to give him a call.

Steve

Chain replacement on Espada or any V12

Hey! Started on one of the chains today. Stuffed a cloth underneath,

took out the clips, didn't loose anything. Hung one end of the chain

over the edge, turned around to fetch the wire to connect to that

end.

I turn around, and then that end of the chain is gone... Oh joy ;)

. I do not understand how it could slip that easily down that

narrow path. Anyway, when thinking about it, the first thing to do,

is

to connect the wire... I bet I remember that the next

time..OK, what's the damage? Is there any way at all to get at the

chain in the bottom there? If the tensioner could be removed, it

seems

likely you will get at it.Or is there a known trick in this

circumstance? Or is the only chance to take the head off? My garage

is

not high enough for that long engine, so I would have to do it with

the

engine in the car.

Looking forward to this one...Cheers, Jarle

Try using a long magnet retrieval tool. Some of them have telescopic

shafts that extend out to several feet. Get the one with the strong

magnet on the end, and you may be able to fish it out. Doc

Jarle, I have dropped it the same way a few times. I normally get it

up

with a hook made out of faily thick stiff wire. You do NOT

have

to take off the tensioner mechanism.Uno

Hi Jarle,Get a good, bright flashlight and you should be able to see

the chain down there. Uno gave you one way to retrieve it and Doc

the

other. I prefer Doc's

strong magnet method and I have one (telescoping) with a very strong

magnet on the end that works every time. Don't feel bad - this has

happened to most of us (but usually only ONCE!!). Cheers, Jack

Hey Doc & Uno! If you ever come to Norway, I am your

personal

guide! I'll buy you beers and dinner too (though it is very

expensive;) With a magnet and some bent wire, I got it up

again! Perfect, thanks! Cheers, Jarle

Hey! I've got one more question for you guys. When working with

these

chains and cam lids, it is dead easy dropping stuff down by the

chains. By looking at photo's it looks like it will mostly end

up

in the oil tray, since it is open all the way down. I am

reluctant about joining the chain, even if I do have a cloth stuffed

there... Anyone ever dropped a link? Think I

will continue tomorrow.. Cheers, Jarle

Again having a lot of old rags pushed around down there before you

put

the link on helps if you drop something small in there, (touch wood,

have never done

this sofar). But as my chain locking link on the first chain

was

missing when I checked my Espada and the one on the second chain was

facing the wrong way, I likely have one small link-lock down there.

:-)

Btw. remember to loosen the chain tensioners before putting in the

new

chain, basically remove the small lock pin, the inner thread

in

it is 3 millimeters (if I remember right, else its 4 mm), so after

having removed the locking nut, put a 3 mm long screw into it and

pull

it out. Now the chain tensioner(s) are loose, this will help you

assemble the new chain, and make the ends meet. Uno